We had an early morning guided tour of the Vatican Museums (and Sistine Chapel). We also saw the gardens and automobile collection (Pope Mobile!), but didn’t go inside St. Peter’s or the crypts. I highly recommend a guided tour of the museums. There’s so much to see, and it’s so much better when you know what it is you’re looking at.

Vatican City

Vatican City, in addition to being the world’s smallest sovereign nation (in both size and population), really is a miniature city. St. Peter’s Basilica and the Vatican Museums dominate the area, but there are many smaller buildings as well.

Luckily we got there with plenty of time to spare, because the walk from the square in front of St. Peter’s to the Museums entrance was a good 20 minute walk, and there was a fairly long line once we got there. We ended up making it inside in time for our timed tour, but barely. Allow plenty of time.

If you’re heading to the Vatican Museums, make sure you’re taking a bus that drops you off on the north side of Vatican City—not the Piazza di San Pietro side to the south. The official address, for the purposes of transit, is Viale Vaticano, 100, Roma 00192. (The internal address is 00120 Vatican City.) The nearest bus stop is Candia/Mocenigo.

Vatican Museums

Bramante Staircase

One of the first things you’ll see on a tour of the Vatican Museums is a spiral staircase known as the Bramante Staircase. The staircase was designed in 1932 by Italian architect Giuseppe Momo to accommodate increased foot traffic.

This version features a double helix structure, allowing people to ascend and descend without crossing paths, a design inspired by the original 1505 staircase conceived by Donato Bramante. (Bramante’s original version was designed for horses and carriages to access the Papal Palace.)

In the second photo you can see the two distinct staircases: to the right, where a person has just entered, is one set of stairs.

To the left you can see the entrance/exit to the second set of stairs. Only one set was open when we were there, possibly because it was early and not yet as crowded as it would no doubt become later in the day.

Fontana della Pigna & the Sphere within a Sphere

We headed outside before deliving deeper into the museums. There was a nice view of the Giardino Quadrato (Square Garden) as well as a contrast of sculptures: the ancient Fontana della Pigna from the 1st century A.D., and the Sphere within a Sphere, from 1990.

The Fontana della Pigna or simply Pigna (“pinecone”) is a former Roman fountain which now decorates a vast niche in the wall of the Vatican facing the Cortile della Pigna (Pinecone Courtyard). Composed of a large bronze pine cone which once spouted water from the top, the Pigna originally stood near the Pantheon next to the Temple of Isis. It was moved to the courtyard of the Old St. Peter’s Basilica during the Middle Ages and then moved again, in 1608, to its present location. The bronze peacocks on either side of the fountain are copies of those decorating the tomb of the Emperor Hadrian, now the Castel Sant’Angelo. The original peacocks are in the Braccio Nuovo Museum.

The Sphere within a Sphere is a bronze statue by Arnaldo Pomodoro, installed at the Vatican in 1990 in the Pinecone Courtyard (Cortile della Pigna). Pomodoro created numerous versions of the Sphere withing a Sphere, all in different sizes, with the version at The Vatican being the largest. They can be seen on display today in places including The Vatican Museums, Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, The U.N Headquarters in New York, Mt. Sinai hospital in New York, Tel Aviv University in Isreal, University of California, Berkley U.S, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts U.S, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art Iowa U.S, Columbus Museum of Art, Iowa, De Young Museum in San Francisco U.S, Hirshhorn Museum in the sculpture garden in Washington D.C and the Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis U.S.

Apollo Belvedere (2nd Century A.D.)

The Apollo Belvedere (also called the Belvedere Apollo, Apollo of the Belvedere, or Pythian Apollo) has been dated to mid-way through the 2nd century A.D. and is considered to be a Roman copy of an original bronze statue created between 330 and 320 B.C. by the Greek sculptor Leochares.

The statue was discovered in Rome in 1489, among the ruins of an ancient domus on the Viminal Hill, and was acquired by Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere. When he was elected pope under the name of Julius II (1503-1513), he had the sculpture moved to the Vatican, where it has been present in the Belvedere since 1508.

The Greek god Apollo is depicted as a standing archer having just shot an arrow, although there is some debate as to what Apollo was shooting. The conventional view has been that he has just slain the serpent Python, the chthonic serpent guarding Delphi—making the sculpture a Pythian Apollo.

The lower part of the right arm and the left hand were missing when discovered and were restored by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (1507–1563), a sculptor and pupil of Michelangelo. However, in the five year restoration that ended in 2024, the left hand was replaced by a copy of the “Hand of Baia”. This hand is an ancient plaster cast of the original statue found in Baia, and therefore was used to make a new left arm more in line with the original.

The face of Apollo inspired the face of Jesus in Michelangelo’s The Last Judgement.

Laocoön and His Sons (aka the Laocoön Group)

The statue of Laocoön and His Sons, also called the Laocoön Group, has been one of the most famous ancient sculptures since it was excavated in Rome in 1506 and put on public display in the Vatican Museums. The statue is very likely the same one praised in the highest terms by Pliny the Elder, the main Roman writer on art, who attributed it to three Greek sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus, although he didn’t say when it was created. Scholars now believe the most likely time period was 27 B.C. to 68 A.D.

The story of Laocoön, a Trojan priest, has been told by numerous Greek writers, though the story differs in each telling. The most famous account of these is now in Virgil’s Aeneid, but this dates from between 29 and 19 BC, which is possibly later than the sculpture. However, some scholars see the group as a depiction of the scene as described by Virgil.

In Virgil, Laocoön was a priest of Poseidon who was killed with both his sons after attempting to expose the ruse of the Trojan Horse by striking it with a spear. In a lost tragedy by Sophocles, he was a priest of Apollo, who should have been celibate but had married. The serpents killed only the two sons, leaving Laocoön himself alive to suffer. In other versions he was killed for having had sex with his wife in the temple of Poseidon, or simply making a sacrifice in the temple with his wife present. Sometimes the snakes were sent by Poseidon, other times by Athena or Apollo. In some stories Laocoön was punished for being wrong, and in others he’s punished for being right.

The Belvedere Torso

The Belvedere Torso is a 1.59-metre-tall (5.2 ft) fragmentary marble statue of a male nude, known to be in Rome from the 1430s, and signed prominently on the front of the base by “Apollonios, son of Nestor, Athenian”. Once believed to be a 1st-century BC original, the statue is now thought to be a copy from the 1st century B.C. or A.D. of an older statue, probably to be dated to the early 2nd century B.C.

Though originally believed to be a statue of Heracles, the Vatican Museum website now states “the most favoured hypothesis identifies it with Ajax, the son of Telamon, in the act of contemplating his suicide”.

The contorted pose and musculature of the torso were highly influential on Renaissance, Mannerist, and Baroque artists, including Michelangelo and Raphael, and it served as a catalyst of the classical revival. Michelangelo’s admiration of the Torso was widely known in his lifetime, and he used it as inspiration for several of the figures on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, including the Sibyls and Prophets along the borders, and both the risen Christ and St. Bartholomew in The Last Judgement.

Hercules Mastai

This gilded bronze statue was found in 1864 beneath the courtyard of the Palazzo Pio Righetti, near Campo de’ Fiori, and in the area of Pompey’s Theatre (where Caesar was assassinated). This is one of only a handful of ancient bronze statues that survived, as ancient Romans melted down most bronze statues to use the valued material elsewhere. The statue shows a young Heracles leaning on his club, with the skin of the Nemean lion over his arm, and the apples of the Hesperides in his left hand.

When the statue was discovered, it was lying on its back in a trench with a slab of travertine on top. Etched onto the travertine were the letters F C S (Fulgur Conditum Summanium). The statue had been struck by lightning, and since Hercules was the son of Zeus, Roman custom at the time meant it should be buried along with the remains of a lamb.

Nero’s Bathtub

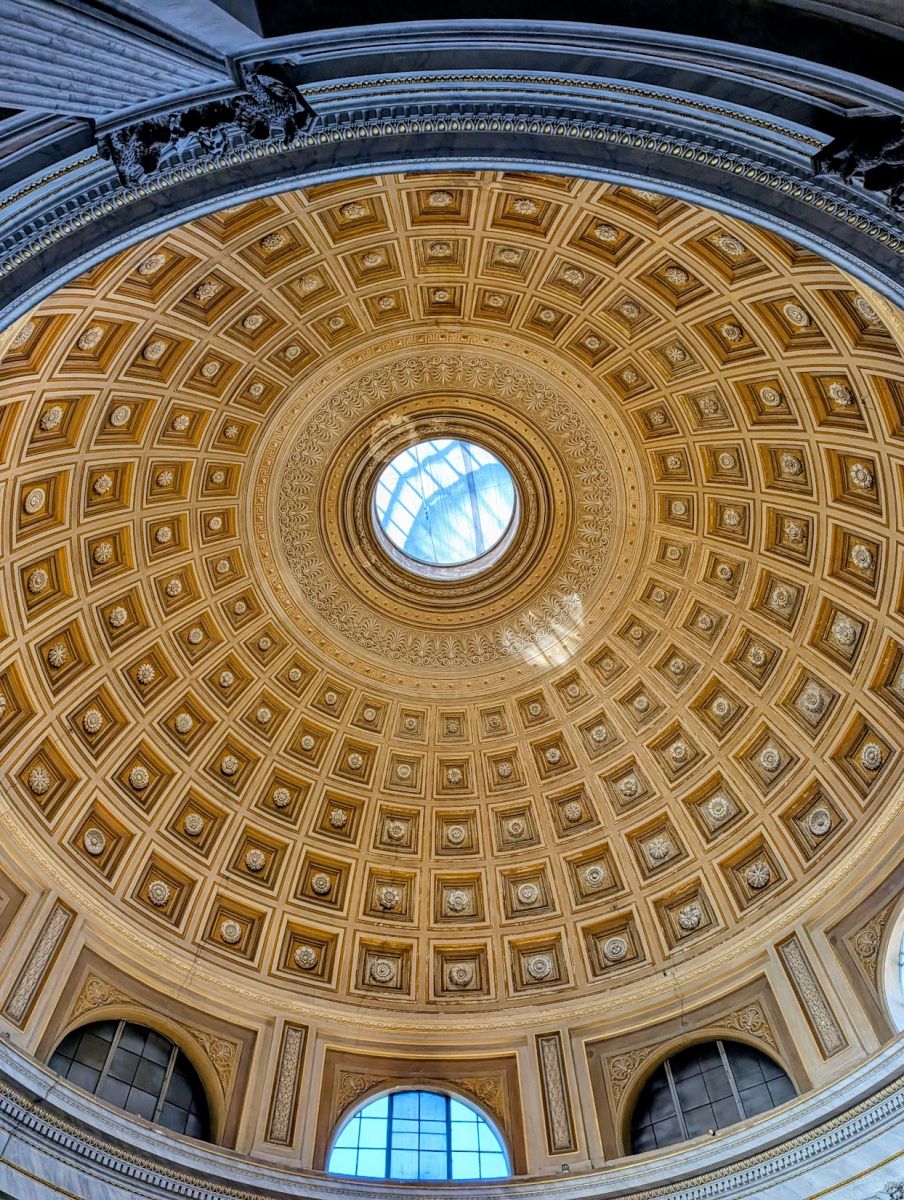

Emperor Nero’s bathtub is a prominent feature in the Round Room (also known as the Sala Rotonda). Commissioned during Nero’s reign (54–68 AD), the bathtub was originally part of his Domus Aurea, or Golden House, a vast palace complex built after the Great Fire of Rome. The tub is carved from a single slab of rare Imperial porphyry, a deep red-purple marble quarried exclusively from a single source in Egypt, which has never been found elsewhere. This material was highly prized in antiquity, symbolizing imperial power and wealth.

The Vatican Museums hold an estimated 80% of the worlds known porphyry, and the size of the tub (and rarity of the material) makes it one of the most valued articles at the Vatican, worth an estimated 2 Billion Euro.

It’s hard to tell the scale from the pictures, but this thing is huge. It measures 25 feet across, with a circumference of 43 feet, and weighs several tons.

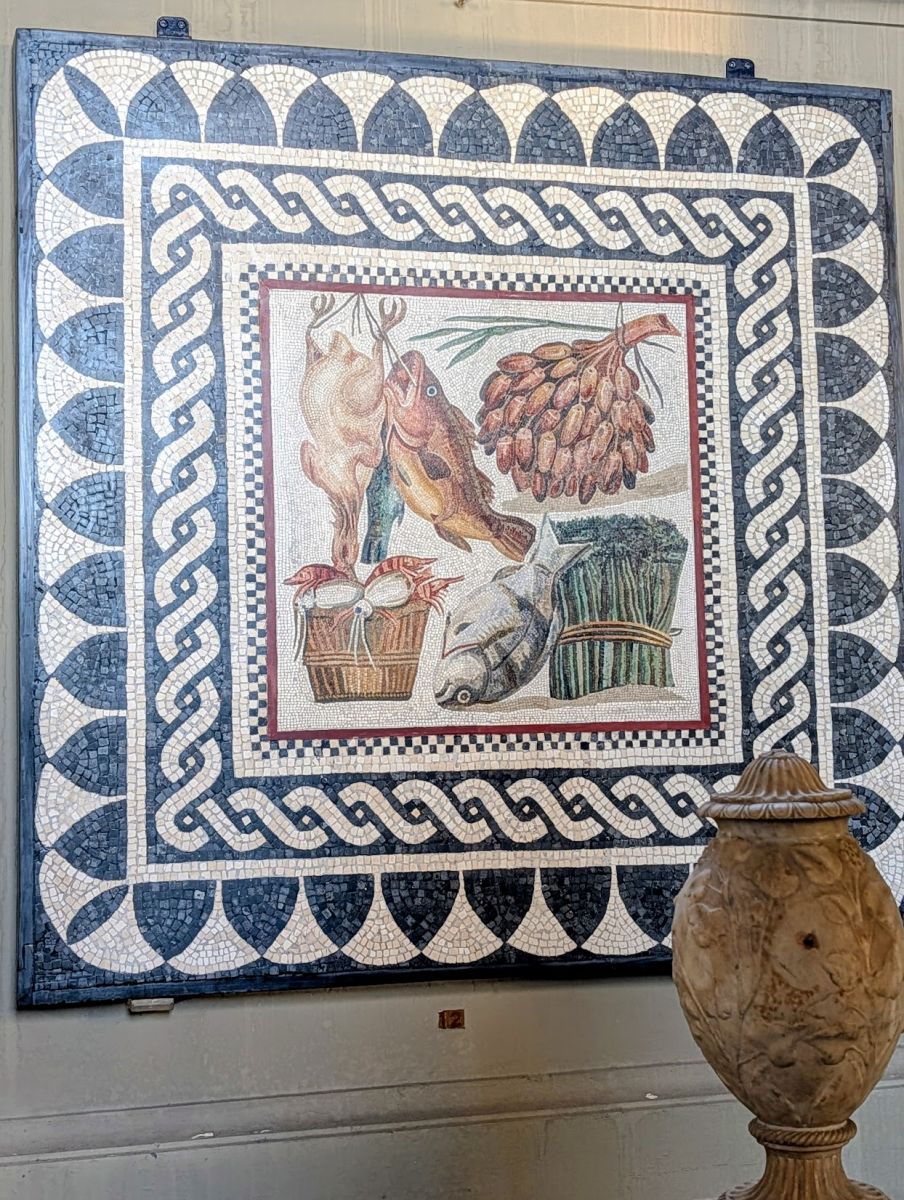

The tub is in the same room as the bronze Hercules statue, a mosaic floor from ancient Ostia Antica depicting the battle of the Centaurs, and several other statues, including those of Antinous and Emperor’s Galba and Claudius.

Sarcophagus Of Saint Helena

The Sarcophagus of Saint Helena is a monumental red porphyry coffin believed to have originally held the remains of Helena, the mother of Emperor Constantine the Great, who died around 335 AD. The sarcophagus was brought into the Vatican in 1777 under Pope Pius VI and restored by Gaspare Sibilla and Giovanni Pierantoni, with its base mounted on four lions carved by Francesco Antonio Franzoni.

Despite its association with Saint Helena, the sarcophagus has been deprived of its original contents for centuries. Helena’s remains were reportedly moved to Santa Maria in Ara Coeli, a basilica on the Capitoline Hill in Rome, which serves as the designated church of the city council.

Satyr with Dionysus/Bacchus as a child

In the Gallery of the Candelabra you’ll find a statue of a young Dionysus (Greek)/Bacchus (Roman) on the shoulders of a satyr. This statue, found in 1854 at the Scala Santa, is noted for its realism and the striking detail of the eyes, which were originally inlaid with marble or painted. Click the photo to really see how creepy the eyes are!

The satyr in this depiction is shown as a companion and helper to Bacchus, a common theme in classical mythology.

The Rafael Rooms

While Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel gets the most press when talking about the Vatican, the frescoes painted by Michelangelo’s contemporary Rafael in what are now referred to as the Rafael Rooms, are also very impressive. The frescoes were commissioned by Pope Julius II at the same time as Michelangelo was working in the Sistine Chapel.

The School of Athens

The School of Athens, a fresco located in the Stanza della Segnatura (Room of the Segnatura), is among the frescoes that are considered by many to signal the beginning of the Golden Age of the High Renaissance, and is considered Rafael’s masterpiece. Each of the four walls in the Stanza della Segnatura has a fresco representing one of the four branches of knowledge at the time—theology, literature, justice, and in the case of The School of Athens, philosophy.

There’s a lot going on in the fresco, and I could devote an entire post to the entire scene, but I’ll instead focus on one aspect—how Rafael painted some of the philosophers with the faces of his contemporaries (and even included a self portrait).

The two main figures in the fresco, placed directly under the archway at the vanishing point of the piece, are Plato and his student Aristotle. It is believed that Rafael used Leonardo da Vinci’s face for Plato, and it’s easy to see the resemblance.

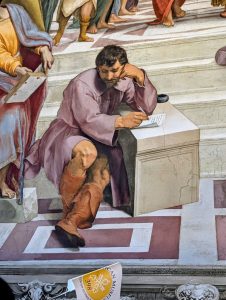

Below Plato is a brooding man seated in the foreground, hand on his head in a classic “thinker” position. The figure is of the philosopher Heraclitus, but it’s widely believed to be a portrait of Michelangelo. The Heraclitus figure was absent in Rafael’s preliminary drawings and sketches, and modern analysis proves it was added later.

The rumor is that after getting a sneak peek at what Michelangelo was doing in the Sistine Chapel, Rafael added the Heraclitus/Michelangelo figure as both a tribute and a dig (Michelangelo and Rafael were rivals), as the figure is done in a very similar style to what Michelangelo was doing in the Sistine Chapel, but was finished first, thus beating Michelangelo to the punch.

On the right side of the fresco, we see Ptolemy (wearing a yellow robe, holding a globe, with his back to the viewer). Just to the right of Ptolemy is a young lad in a dark cap staring side-eyed at the viewer. That’s a self portrait of Rafael himself.

To the left of Ptolemy (see the full fresco above), leaning over, is Italian architect and painter Bramante as Euclid.

On the wall opposite The School of Athens is a fresco representing theology—The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament. For some reason I only captured the top half of the fresco, representing the celestial sphere. I completely cut out the bottom half, representing the earthly sphere.

There are many other Rafael frescoes, but those I liked best were Encounter of Leo the Great with Attila, and Fire in the Borgo.

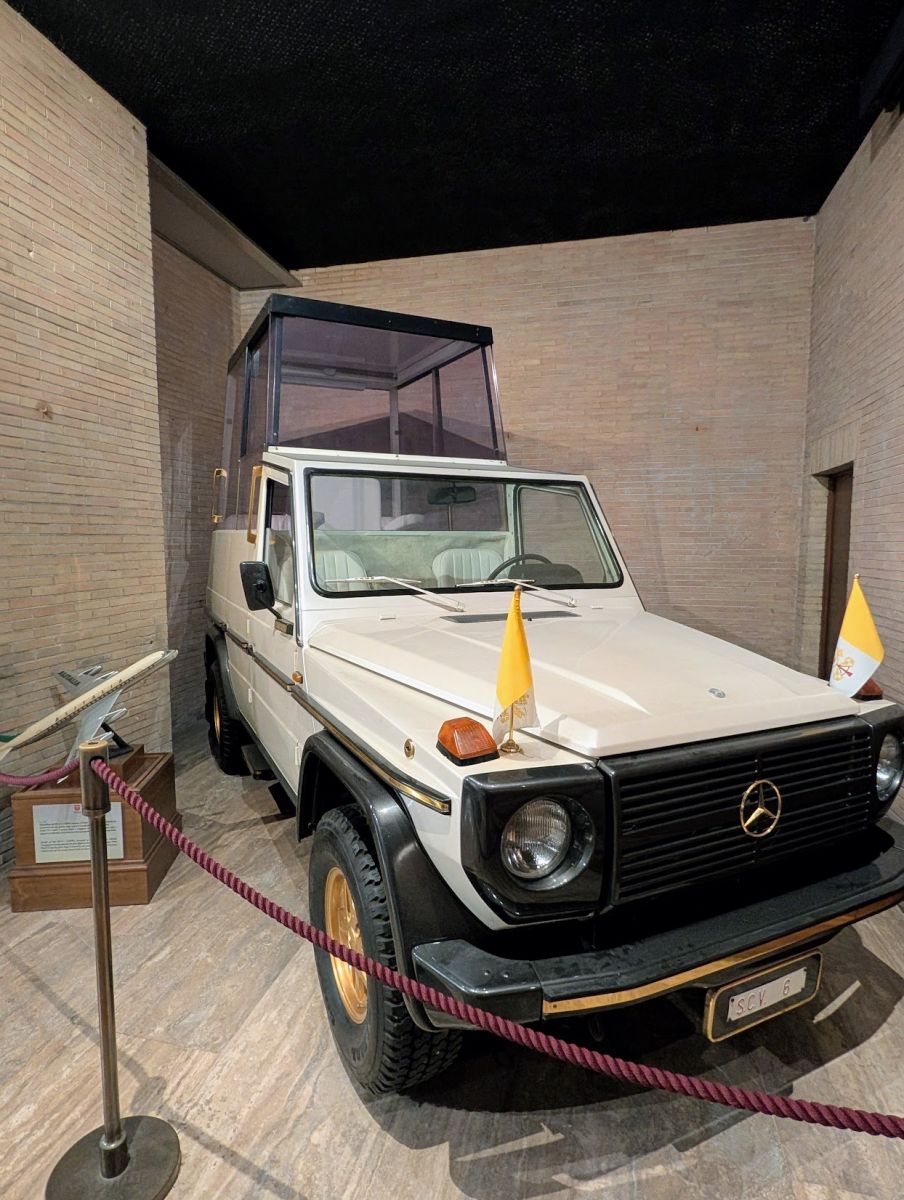

Carriage Pavilion

The last thing we checked out at the Vatican was the Carriage Pavilion—a collection of carriages and cars that have carried Popes around for hundreds of years. It was a fun exhibit. To find it, look for the elevator in the Giardino Quadrato.

There will be a ton more Vatican Museums photos at the end of the post in the Photo Dumps section.

Sistine Chapel

No photos or video are allowed in the Sistine Chapel, and I didn’t try to sneak any. You need to see it to appreciate it. We could have spent an hour staring at the ceiling. One detail that I appreciated are the small patches of soot-covered ceiling they left un-cleaned when they renovated in the 80’s and 90’s. Over the centuries, the smoke from candles in the chapel stained the ceiling almost black. When they cleaned it, they left a handful of square patches so you can see how dramatic the difference is between clean and un-cleaned.

The Vittoriano (aka Altar of the Fatherland, aka Victor Emmanuel II National Monument)

Later in the afternoon, I went to the top of the Altar of the Fatherland, also known as the Victor Emmanuel II National Monument, also known as Vittoriano. It’s a huge monument, built 1885 and 1935 to honour Victor Emmanuel II, the first king of a unified Italy. It sits at the head of Piazza Venezia (which was under construction while we were there—the entire piazza was fenced off). The views from the top were stunning.

From an architectural perspective, it was conceived as a modern forum, an agora on three levels connected by stairways and dominated by a portico characterized by a colonnade. There’s a shrine of the Italian Unknown Soldier, thus adopting the function of a secular temple consecrated to Italy. Because of its great representative value, the entire Vittoriano is often called the Altare della Patria (Altar of the Fatherland), although the latter constitutes only a part of the monument.

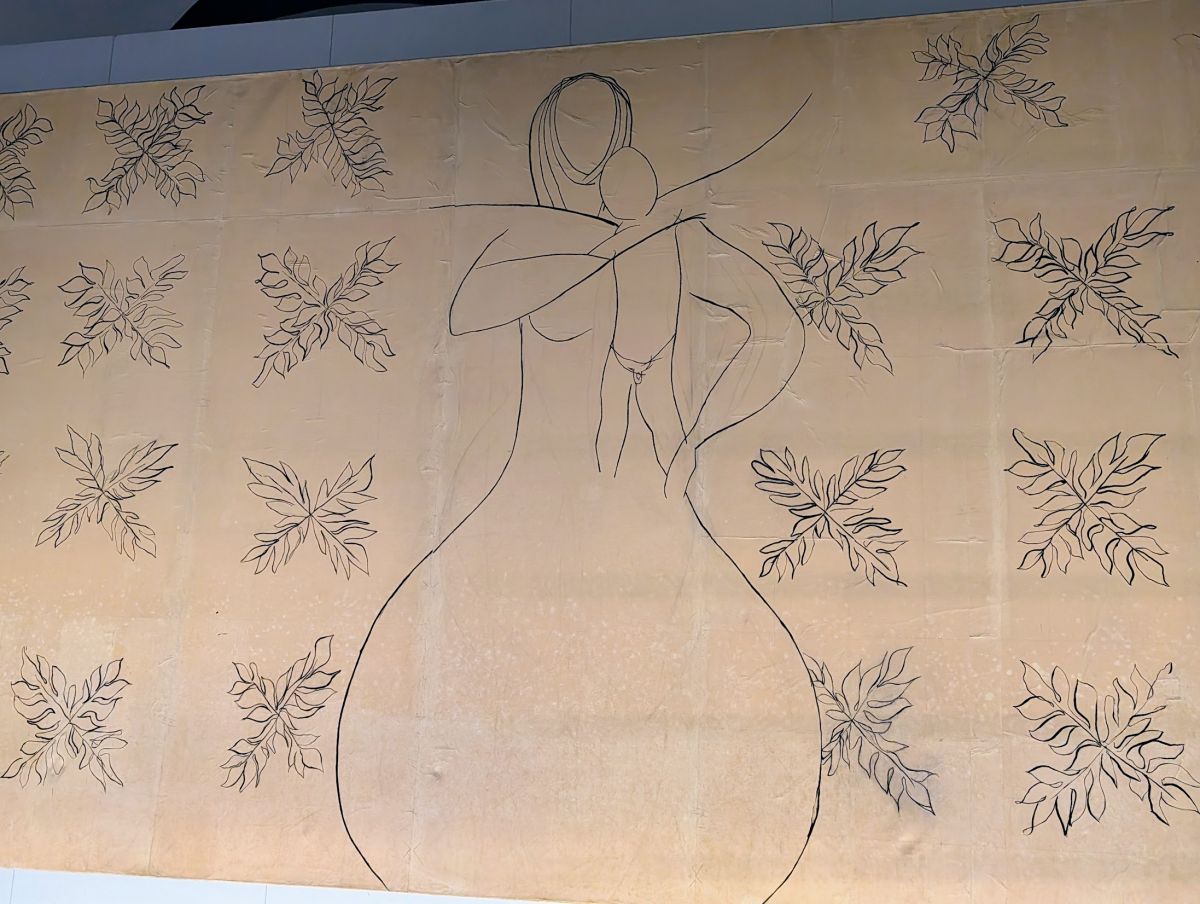

Alphonse Mucha Exhibit

While I explored the Vittoriano, Teresa visited the exhibition “Alphonse Mucha: A Triumph of Beauty and Seduction” at Palazzo Bonaparte, on the other end of Piazza Venezia. She loved the exhibit, which runs until March 8, 2026. If you’re going to Rome between now and then, you should check it out.

Oro Bistrot

After a quick drink at Cafè Bristrot/Vini we headed to Oro Bistrot for an early/light dinner. We were able to get a table without a reservation after a short wait. If going later in the evening, you’ll probably need reservation, as the space is fairly small and the views are incredible. The duomo of the church with the longest name (Church of the Most Holy Name of Mary at the Forum of Trajan) is basically at eye level, and so close you feel like you can tough it.

We had some very good focaccia with mortadella, steak tartare, and an assortment of chips, nuts, and crackers. (As well as cocktails.)

Beautiful and so thoroughly researched. Do you want Mucha photos?

Yes, please! Add them to the shared gallery.

Gorgeous pics!